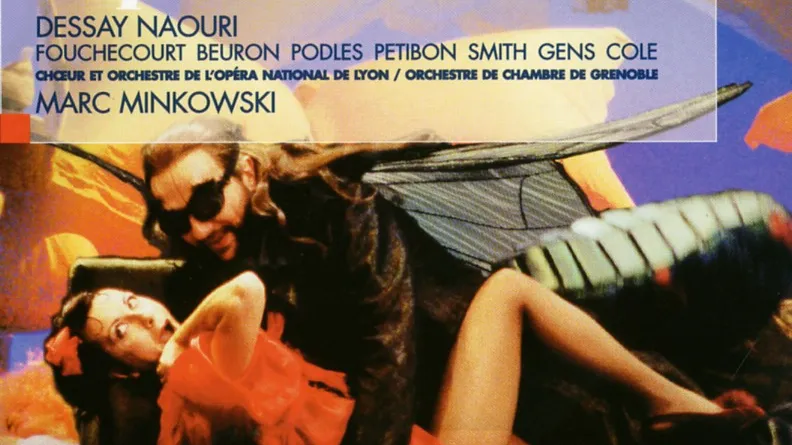

ORPHEE AUX ENFERS (Offenbach) Lyon 1997 Natalie Dessay, Yann Beuron, Laurent Naouri

In this video

ORPHEE AUX ENFERS by Jacques Offenbach

Opera national de Lyon, France

1997

CAST

Natalie Dessay – Eurydice

Yann Beuron – Orphée

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt – Aristée/Pluton

Laurent Naouri – Jupiter

Martine Olméda – L’Opinion Publique

Steven Cole – John Styx

Cassandre Berthon – Cupidon

Ethienne Lescroart – Mercure

Virginie Pochon – Diane

Lydie Pruvot – Junon

Maryline Fallot – Vénus

Alketa Cela – Minerve

____________________________________________

Conductor: Marc Minkowski

Orchestre de l’Opéra de Lyon,

Grenoble chamber orchestra

Chœurs de l’Opéra de Lyon

Choreographer: Dominique Boivin

____________________________________________

Stage Director: Laurent Pelly

Stage Designer: Chantal Thomas

Costume Designer: Laurent Pelly

Lighting Designer: Joël Adam

============================================

Orpheus in the Underworld[1] and Orpheus in Hell[2] are English names for Orphée aux enfers (French: [ɔʁfe oz‿ɑ̃fɛʁ]), a comic opera with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy. It was first performed as a two-act “opéra bouffon” at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, Paris, on 21 October 1858, and was extensively revised and expanded in a four-act “opéra féerie” version, presented at the Théâtre de la Gaîté, Paris, on 7 February 1874.

The opera is a lampoon of the ancient legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. In this version Orpheus is not the son of Apollo but a rustic violin teacher. He is glad to be rid of his wife, Eurydice, when she is abducted by the god of the underworld, Pluto. Orpheus has to be bullied by Public Opinion into trying to rescue Eurydice. The reprehensible conduct of the gods of Olympus in the opera was widely seen as a veiled satire of the court and government of Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. Some critics expressed outrage at the librettists’ disrespect for classic mythology and the composer’s parody of Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice; others praised the piece highly.

Orphée aux enfers was Offenbach’s first full-length opera. The original 1858 production became a box-office success, and ran well into the following year, rescuing Offenbach and his Bouffes company from financial difficulty. The 1874 revival broke records at the Gaîté’s box-office. The work was frequently staged in France and internationally during the composer’s lifetime and throughout the 20th century. It is one of his most often performed operas, and continues to be revived in the 21st century.

In the last decade of the 19th century the Paris cabarets the Moulin Rouge and Folies Bergère adopted the music of the “Galop infernal” from the culminating scene of the opera to accompany the can-can, and ever since then the tune has been popularly associated with the dance.

Synopsis

Original two-act version

Act 1, Scene 1: The countryside near Thebes, Ancient Greece

A spoken introduction with orchestral accompaniment (Introduction and Melodrame) opens the work. Public Opinion explains who she is – the guardian of morality (“Qui suis-je? du Théâtre Antique”).[28] She says that unlike the chorus in Ancient Greek plays she does not merely comment on the action, but intervenes in it, to make sure the story maintains a high moral tone. Her efforts are hampered by the facts of the matter: Orphée is not the son of Apollo, as in classical myth, but a rustic teacher of music, whose dislike of his wife, Eurydice, is heartily reciprocated. She is in love with the shepherd, Aristée (Aristaeus), who lives next door (“La femme dont le coeur rêve”),[29] and Orphée is in love with Chloë, a shepherdess. When Orphée mistakes Eurydice for her, everything comes out, and Eurydice insists they abandon the marriage. Orphée, fearing Public Opinion’s reaction, torments his wife into keeping the scandal quiet using violin music, which she hates (“Ah, c’est ainsi”).[30]

Aristée enters. Though seemingly a shepherd he is in reality Pluton (Pluto), God of the Underworld. He keeps up his disguise by singing a pastoral song about sheep (“Moi, je suis Aristée”). Eurydice has discovered what she thinks is a plot by Orphée to kill Aristée – letting snakes loose in the fields – but is in fact a conspiracy between Orphée and Pluton to kill her, so that Pluton may have her and Orphée be rid of her. Pluton tricks her into walking into the trap by showing immunity to it, and she is bitten. As she dies, Pluton transforms into his true form (Transformation Scene).[33] Eurydice finds that death is not so bad when the God of Death is in love with one (“La mort m’apparaît souriante”). They descend into the Underworld as soon as Eurydice has left a note telling her husband she has been unavoidably detained.

All seems to be going well for Orphée until Public Opinion catches up with him, and threatens to ruin his violin teaching career unless he goes to rescue his wife. Orphée reluctantly agrees.

Act 1, Scene 2: Olympus

The scene changes to Olympus, where the Gods are sleeping (“Dormons, dormons”). Cupidon and Vénus enter separately from amatory nocturnal escapades and join their sleeping colleagues,but everyone is soon woken by the sound of the horn of Diane, supposedly chaste huntress and goddess. She laments the sudden absence of Actaeon, her current love (“Quand Diane descend dans la plaine”); to her indignation, Jupiter tells her he has turned Actaeon into a stag to protect her reputation. Mercury arrives and reports that he has visited the Underworld, to which Pluton has just returned with a beautiful woman.[41] Pluton enters, and is taken to task by Jupiter for his scandalous private life. To Pluton’s relief the other Gods choose this moment to revolt against Jupiter’s reign, their boring diet of ambrosia and nectar, and the sheer tedium of Olympus (“Aux armes, dieux et demi-dieux!”). Jupiter’s demands to know what is going on lead them to point out his hypocrisy in detail, poking fun at all his mythological affairs (“Pour séduire Alcmène la fière”).

Orphée’s arrival, with Public Opinion at his side, has the gods on their best behaviour (“Il approche! Il s’avance”). Orphée obeys Public Opinion and pretends to be pining for Eurydice: he illustrates his supposed pain with a snatch of “Che farò senza Euridice” from Gluck‘s Orfeo. Pluton is worried he will be forced to give Eurydice back; Jupiter announces that he is going to the Underworld to sort everything out. The other gods beg to come with him, he consents, and mass celebrations break out at this holiday (“Gloire! gloire à Jupiter… Partons, partons”).

Act 2, Scene 1: Pluton’s boudoir in the Underworld

Eurydice is being kept locked up by Pluton, and is finding life very tedious. Her gaoler is a dull-witted tippler by the name of John Styx. Before he died, he was King of Boeotia (a region of Greece that Aristophanes made synonymous with country bumpkins), and he sings Eurydice a doleful lament for his lost kingship (“Quand j’étais roi de Béotie”).

Jupiter discovers where Pluton has hidden Eurydice, and slips through the keyhole by turning into a beautiful, golden fly. He meets Eurydice on the other side, and sings a love duet with her where his part consists entirely of buzzing (“Duo de la mouche”).[50] Afterwards, he reveals himself to her, and promises to help her, largely because he wants her for himself. Pluton is left furiously berating John Styx.

Act 2, Scene 2: The banks of the Styx

The scene shifts to a huge party the gods are having, where ambrosia, nectar, and propriety are nowhere to be seen (“Vive le vin! Vive Pluton!”). Eurydice is present, disguised as a bacchante (“J’ai vu le dieu Bacchus”), but Jupiter’s plan to sneak her out is interrupted by calls for a dance. Jupiter insists on a minuet, which everybody else finds boring (“La la la. Le menuet n’est vraiment si charmant”). Things liven up as the most famous number in the opera, the “Galop infernal”, begins, and all present throw themselves into it with wild abandon (“Ce bal est original”).

Ominous violin music heralds the approach of Orphée (Entrance of Orphée and Public Opinion), but Jupiter has a plan, and promises to keep Eurydice away from her husband. As with the standard myth, Orphée must not look back, or he will lose Eurydice forever (“Ne regarde pas en arrière!”). Public Opinion keeps a close eye on him, to keep him from cheating, but Jupiter throws a lightning bolt, making him jump and look back, and Eurydice vanishes. Amid the ensuing turmoil, Jupiter proclaims that she will henceforth belong to the god Bacchus and become one of his priestesses. Public Opinion is not pleased, but Pluton has had enough of Eurydice, Orphée is free of her, and all ends happily.

Revised 1874 version

The plot is essentially that of the 1858 version. Instead of two acts with two scenes apiece, the later version is in four acts, which follow the plot of the four scenes of the original. The revised version differs from the first in having several interpolated ballet sequences, and some extra characters and musical numbers. The additions do not affect the main narrative but add considerably to the length of the score.[n 14] In Act I there is an opening chorus for assembled shepherds and shepherdesses, and Orpheus has a group of youthful violin students, who bid him farewell at the end of the act. In Act 2 Mercure is given a solo entrance number (“Eh hop!”). In Act 3, Eurydice has a new solo, the “Couplets des regrets” (“Ah! quelle triste destinée!”), Cupidon has a new number, the “Couplets des baisers” (“Allons, mes fins limiers”), the three judges of Hades and a little band of policemen are added to the cast to be involved in Jupiter’s search for the concealed Eurydice, and at the end of the act the furious Pluton is seized and carried off by a swarm of flies.

Quoted from Wikipedia